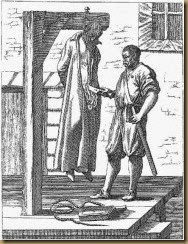

In the year 1678 the enemies of Catholicity in England, anxious to make a last assault on the Church of their fathers, entered into a conspiracy as dark and as hideous as any known in history. The chief agent in this plot was Titus Oates, whose name has been attached to it by posterity. He had been a clergyman of the Established Church, but preferred to his benefice an infamous and vagrant life. Under ever-varying disguises he insinuated himself into some religious houses on the continent, and made himself sufficiently acquainted with Catholic usages and distinguished Catholic names to be able to give a semblance of circumstantial accuracy to any anti-Catholic tale which he might devise. Returning to England, he found the Protestant populace in a ferment lest a Papist should succeed to the royal throne, and he soon learned that the leaders of the opposition _ were eager to second and repay each effort to fan the flame. Such was, then, the disposition of mens' minds, that the monstrous romance which he constructed was hailed with applause, and found credence, not only with the vulgar, but even with the most sober members of the king's council. The Pope, he said, had handed over the government of England to the Jesuits, and these had already, by commissions under the great seal of the society, appointed to all the chief offices in church and state. Once before the Papists had burned London: that scene was to be now renewed, whilst in the confusion they would assassinate the king, and, at a given signal, each Catholic should massacre his Protestant neighbours.

This tale was not merely greeted with applause. Oates became the idol of the people, and through the influence of his patrons, was raised on a sudden from obscurity and poverty to a position of dignity and wealth Hence he soon found associates and rivals. To give perjured evidence, and lead Catholics to the scaffold, had proved a good speculation, and many wished to share in its profits and honours. We shall allow a Protestant historian to trace the character of the principal of these informers. "A wretch named Carstairs, who had earned a living in Scotland, by going disguised to conventicles, and then informing against the preachers, led the way: Bedloe, a noted swindler, followed; and soon, from all the brothels, gambling-houses, and spunging houses of London, false witnesses poured forth, to swear away the lives of Roman Catholics. One came with the story, of an army of thirty thousand men, who were to muster in the disguise of pilgrims, at Corunna, and to sail thence to Wales. Another had been promised canonization and five hundred pounds to murder the king.

Oates, that he might not be eclipsed by his imitators, soon added a large supplement to his original narrative. The vulgar believed, and the highest magistrates pretended to believe even such fictions as these. The chief judges of the kingdom were corrupt, cruel, and timid... . The juries partook of the feelings then common throughout the nation, and were encouraged by the bench to indulge those feelings without restraint. The multitude applauded Oates and his confederates, hooted and pelted the witnesses who appeared on behalf of the accused, and shouted with joy when the verdict of guilty was pronounced." And hence, as the same writer had already remarked, the courts of justice, "which ought to be sure places of refuge for the innocent of every party, were disgraced by wilder passions and fouler corruptions'' than could be found in the annals of England.

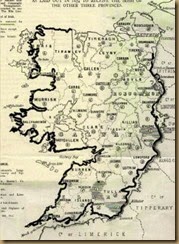

Such an excitement against the Catholics naturally found a response in the Protestant ascendancy of Ireland. Ormond was, at this time, Viceroy; his private letters, indeed, prove that he gave no credence to the accusations against the Catholics, but, nevertheless, with his usual duplicity, he enacted such measures and laws as supposed and confirmed the belief of the reality- of their treasonable designs. The council of Ireland met in the presence of the Viceroy, on the 14th of October, 1678. Their first enactment was, that all officers and soldiers should repair without delay to their respective garrisons. A proclamation ensued, commanding "all titular Popish bishops and dignitaries, and all others exercising ecclesiastical jurisdiction by authority from the See of Rome, all Jesuits and other regular priests," to depart from the kingdom before the 20th of November following; whilst a reward was offered of £10 for the capture of a bishop, and £5 for that of a regular, after that period. Orders were, at the same time, given, that all "Popish societies, convents, seminaries, and schools," should be forthwith dissolved and utterly suppressed.

To prevent all excuses for not obeying the foregoing proclamation, another was issued on the 16th of November, requiring all owners and masters of ships bound for foreign parts to receive "the Popish clergy" on board, and to transport them accordingly.

It was deemed necessary, too, to disarm the Catholics; and a special-proclamation enacted, that "no persons of the Popish religion should carry, buy, use, or keep in their houses any arms without license; and that all justices of the peace should search for such arms as were not brought in within twenty days, and bind over the offenders to be prosecuted at the next assizes.''

It was feared, however, that some officers were remiss in executing these laws, and hence positive orders were further issued on the 2nd of December, by the Lord Lieutenant and council, addressed to the sheriffs of the several counties, and to be by them communicated to the justices of the peace, " taking notice of their neglect in not apprehending such of the Popish regular clergy as did not transport themselves, and requiring them to return, not only their names, but the names also of such as received, relieved, and harboured them." They were, moreover, required to return " the names of all persons licensed to carry arms, and to prosecute those who had not delivered in their arms" according to preceding proclamations.

These orders were principally directed against the prelates and regulars, but in reality the officers commissioned with their execution prosecuted alike the secular clergy; it was enough for them to raise the cry that any one was a Jesuit in disguise to obtain their reward. A proclamation, however, published on the 26th of March, 1679, had the secular clergy for its special object. It commanded "that when there was any Popish pretended parish priest of any place where any robbery or murder was committed by the tories he should be seized upon, committed to the common gaol, and thence transported beyond the seas, unless within fourteen days after such robbery or murder the persons guilty thereof were either killed or taken, or such discovery made thereof in that time, as the offenders might therefore be apprehended and brought to justice."

A further proclamation ordered the suppression of "Mass-houses and meetings for Popish services in the cities and suburbs of Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Waterford, Kinsale,Wexford, Athlone, Ross, Galway, Drogheda, Youghall, Clonmel, and Kilkenny," these being the most considerable towns in the kingdom, "in which too many precautions could not be taken"

No soldier had for many years been admitted to the army till he had taken the oaths of allegiance and supremacy. It was now rumoured that some, after entering the service, had embraced the Catholic religion, and hence a special proclamation offered rewards " for the discovery of any officer or soldier who had heard Mass or been so perverted to the Popish religion." On the same day with this proclamation (20th November, 1678), another was issued, prohibiting all Catholics, "from entering the Castle of Dublin, or any other fort or citadel," and ordering that "no persons of the Romish religion" should be suffered to reside in the towns of Drogheda, Wexford, Cork, Limerick, Waterford, Youghall, and Galway, or in any other corporation, excepting such as " for the greatest part of the twelve months past had inhabited them."

The result of such stringent measures, though, perhaps, it did satisfy the cravings of those who had anxiously looked forward to the rooting out of Catholicity from the "Island of Saints," yet was such as even to surpass the expectations of moderate Protestants, and Carte remarks, that though all the clergy were not expelled from the kingdom, " which never was, and never will be, the consequence of a proclamation; yet more had been shipped off than could have been imagined, and the rest lurked in corners, and durst not come near the great towns." (Ibid. 483.)

The illustrious Archbishop of Dublin, Dr. Talbot, returned to England from his exile on the continent in 1676, and a few months before the present outburst of feeling against the Catholics, through the intercession of the Duke of York, obtained permission to revisit and console his spiritual flock. Though subject to violent disease, and apparently at the close of his eventful career, yet was he chosen by the malignant policy of Ormond to be the first Irish victim of the persecution. Dr. Plunket announces his arrest, writing on the 27th of October, 1678:—

"The matter being proposed and discussed in the Provincial Council that I should make a visitation of the province, I commenced with Meath, which is the first suffragan diocese, and then proceeded to the diocese of Clonmacnoise, where I had scarcely finished when the news arrived by post, that Dr. Talbot of Dublin was arrested and imprisoned in the Castle or Tower of this city. I received this news on the 21st of the past month; immediately afterwards came a proclamation or edict, banishing all the archbishops, bishops, vicars-general, and all the regulars, commanding them to leave the kingdom before the 20th of November, and threatening penalties and fines against any secular who would give them to eat or drink, or otherwise assist them. I was quite astonished at the arrest of the Archbishop of Dublin, the more so, as since his return to Ireland he did not perform any ecclesiastical function.

"The convents of the poor regular clergy have been all scattered and destroyed; so that all the disputes and the reforms which were in contemplation for them are all terminated by this edict. The parish priests and secular priests are not included in it. It is not known what particular accusation has been made against the Archbishop of Dublin; he is in the secret prison, and no one is allowed to hold communication with him. Some have been imprisoned in London on suspicion of conspiracy against the king, and for maintaining private correspondence with foreign princes, and for the murder of a nobleman who was found dead in London. As to the conspiracy against the king, it is a merely imaginary one. I have not been included by name in the present edict, nor in that passed four years ago, and, therefore, I will remain in the kingdom, though retired in some country place, and it is probable that Dr. Brennan and I shall be together.

Taken from - MEMOIRS OF THE MOST REV. OLIVER PLUNKET, WHO SUFFERED DEATH FOR THE CATHOLIC FAITH IN THE YEAR 1681.