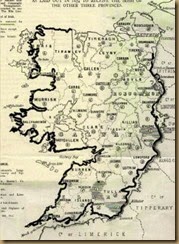

Map of Clare as laid out in 1654 to receive the Irish

of the three other provinces. Link

§ 5.—Transplanting To Connaught.

The sword, and subsequent persecuting edicts, did not succeed in exterminating the Catholic Irish. Hence, the ingenuity of the Puritan masters was set to work to discover some new means for attaining that end. A spot was chosen, the most desolate and devastated in the whole kingdom, and thither, by public proclamation, (in 1654,) all Catholics were commanded to repair. This was, in fact, nothing less than a frightful imprisonment of all the survivors of the nation. To Connaught or the scaffold, was the fiendish cry of the persecutors throughout the country; and yet it was not even the province of Connaught, but only the barren portions of it that the bounty of the Puritans set aside for the Irish Catholics. The heretics retained for themselves a breadth of four miles along the shores of the Atlantic, and of two miles along the rich banks of the Shannon. The Irish, moreover, were not allowed to reside in the capital of the province, or in any of the market-towns. Pent up within these precincts, it was expected that the Catholic race would soon become extinct by famine and disease; for throughout this barren district the new-comers were friendless and unpitied, without food to eat or house to afford them a protection; there was no seed to sow, nor cattle to stock the land. It was death for an Irishman to step beyond the limits thus cruelly traced, and any mere Irishman found in any other part of the kingdom could be butchered without further inquiry. We shall allow Lord Clarendon to sketch this refinement of Puritan policy:—

"They found the utter extermination of the nation which they had intended, to be in itself very difficult, and to carry in it somewhat of horror, that made some impression upon the stone-hardness of their own hearts. After so many thousands destroyed by the plague which raged over the kingdom, by fire, sword, and famine, and after so many thousands transported to foreign parts, there remained still such a numerous"people, that they knew not how to dispose of; and though they were declared to be all forfeited, and so to have no title to anything, yet they must remain somewhere; they therefore found this expedient, which they called an Act of grace. There was a large tract of land, even to the half of the province of Connaught, that was separated from the rest by a long and large river, and which by the plague, and many massacres, remained almost desolate. Into this space they required all the Irish to retire by such a day, under the penalty of death; and who should after that time be found in any other part of the kingdom, man, woman, or child, should be killed by anybody who saw or met them. The land within the circuit, the most barren in the kingdom, was, out of this grace and mercy of the conquerors, assigned to those of the nation as were enclosed, in such proportions as might -with great industry preserve their lives."— (Clarendon's Life, vol. ii. p. 116.)*

The persecutors, however, were not satiated by thus transplanting the Irish inhabitants; they, moreover, obliged all to whom some portions of land were marked out in this barren district, to sign conveyances or releases of their titles to their former properties, that thus they and their heirs might be for ever debarred from their old inheritance. This law was not a mere idle threat; it was carried into execution with the greatest rigour. Amongst other instances we find recorded, that when some of the transplanted Irish erected cabins or creaghts, as the hurdle houses were then called, in the vicinity of Athlone, orders were sent from Dublin Castle to banish all the Irish and other popish persons from that neighbourhood, so that no such gathering should be allowed within five miles of the English garrison.

No pen can describe the frightful scenes of misery that ensued. With famine and pestilence, despair seized upon the afflicted natives; thousands died of starvation and disease; others cast themselves from precipices, whilst the walking spectres that remained seemed to indicate that the whole plantation was nothing more than a mighty sepulchre.

The Puritans, however, were still attentive to extort from the poverty of the transplanted Catholics whatsoever might perchance, have yet remained to them. A contemporary writer thus describes these new arts of the Puritan persecutors:—

"There is one thing that now perplexes us very much, the transplanting of our nation to the province of Connaught. This is a tract of Ireland for the most part rocky and mountainous, and wholly reduced to a wilderness by the constant whirlwind of wars, uninterrupted for so many years. Nowhere, throughout all that region, can a house be met with; scarcely is there a particle of a wall left standing, the edifices being destroyed by fire, and levelled to the ground, lest any habitation or defence should remain for the Catholics. Two cities alone remain, and from these the inhabitants are expelled, and they are now filled with English Anabaptists; some of the maritime ports, too, are inhabited by the same pest; the remainder of the province is wholly devastated, and everything levelled to the ground.

"To this desert all the nobility and gentry of the kingdom, and all that had any land or possessions are now transported; amidst these mountains they receive some small particles of land, for the most part sterile and rocky. There they must fix their dwellings, and build for themselves, as best they may, or otherwise be exposed to the hoar frost. Nor is the evil confined to this. The Catholics thus transplanted, although deprived of nearly all their fortunes and goods, are, nevertheless, obliged to support in this Connaught wilderness seventy stations of Puritan soldiers, which are arranged at stated distances throughout the country, under the pretence, indeed, of their own security, and lest Catholics might plot against the State, and excite fresh disturbances, but in reality that they may keep away all priests, and prevent the exercise of the Catholic religion; and, moreover, that thus any property that still remained amongst the persecuted natives might be wasted away and consumed in supporting such a number of guards, and so the whole nation might become gradually extinct; for they see that no violence or artifice can force them to abandon the Catholic faith. Indeed, the magistrates more than once notified to some of the Catholic gentry whom they were anxious to protect, that all this vexation would cease, should they only consent to renounce the Roman Pontiff, and especially the Mass. They sought also to persuade not a few of the Catholics, that it was folly for them to precipitate themselves into voluntary banishment, which could be prevented by so easy a remedy. But the Catholics closed their ears with the holy fear of God against these Siren enchantments, and they choose to suffer even death rather than to tarnish their glory, holding in mind that they are children of saints, and that an inheritance of glory awaits them."

Taken from - MEMOIRS OF THE MOST REV. OLIVER PLUNKET, WHO SUFFERED DEATH FOR THE CATHOLIC FAITH IN THE YEAR 1681.