§ 4.—Perils Of The Clergy.

The reader can now easily picture to himself the perils that on every side beset the Irish priesthood. Yet, heedless of danger, many clung to their flocks to break to them the bread of life. History does not afford examples of more heroic fortitude, more fearless courage, more enduring constancy, than that displayed at this period by the Catholic clergy of Ireland. Mr. Dalton, in his history of the Archbishops of Dublin, quotes from a Latin manuscript, written in 1653, the following extract :—

"The keen eyed vigilance of persecution has driven the Catholic laity into the country; and the priests and monks scarcely presume to sleep even in the houses of their own people; their life is warfare and earthly martyrdom ; they breathe as if by stealth among the hills or in the woods, and not un frequently in the abyss of bogs or marshes, which their oppressors cannot penetrate; yet, hither flock congregations of poor Catholics, whom they refresh with the consolation of the sacraments, direct with the best advice, instruct in constancy of faith and confirm in the endurance of the cross of the Lord. These things, however, could not be effected without the knowledge of the heretics, who in a simultaneous impulse are hurried through the mountains and the woods exploring the retreat of the clergy; and never was the chase of the wild beasts more hot and more bitter than the rush of the priest-destroyers through the woods of Ireland, many of whom deem it the most agreeable recreation to run down to the death those beasts of the woods, as they term the Catholic clergy."

The narrative of the state of Ireland in 1654, presents many additional particulars:—

"We live, for the most part, in the mountains and forests; and often, too, in the midst of bogs to escape the horse of the heretics. One priest, advanced in years, father John Carolan, was so diligently sought for, and so closely watched, being surrounded on all sides, and yet not discovered, that at length he died of starvation. Another, father Christopher Netterville, like St. Athanasius, for an entire year and more, lay hid in his father's sepulchre; and even there with difficulty escaping the pursuit of the enemy, he had to fly to a still more incommodious retreat. One was concealed in a deep pit, from which he at intervals went forth on some mission of charity. The heretics having received information as to his hiding-place, rushed to it, and throwing down immense blocks of rock, exulted in his destruction; but Providence watched over the good father, and he was absent, engaged in some pious work of his sacred ministry, when his retreat was thus assailed. As the holy Sacrifice cannot be offered up in these receptacles of beasts rather than of men, all the clergy carry with them a sufficient number of consecrated hosts, that thus they themselves may be comforted by this holy Sacrament, and may be able to administer it to the sick and to others."

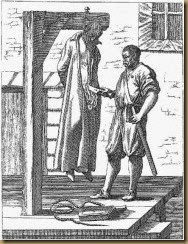

Every art of the most refined cruelty was deemed lawful when pursuing to death these doomed victims of the Catholic clergy; and many are the instances which have been handed down to us of priests who were dragged from their hidden recesses, and subjected to the most brutal excesses. One scene, recorded by Ludlow in his memoirs (vol. 1; page, 422; edition Vevay, 1698), sufficiently illustrates the rage of the persecutors.

When marching from Dundalk to Castleblaney, and passing by a deep cave, he discovered that some Irish were concealed therein. Two days were spent by his party in endeavouring to smother the fugitives by smoke. At the close of the first day, thinking that all should be dead, some of them entered the mouth of the cave, but as they advanced, the foremost was wounded by a pistol-shot fired from within. It appears that the inmates preserved themselves from suffocation by holding their faces close to the surface of some running water in the cavern; and one, who was placed at the entrance as guard, took his post near a crevice through which the air was admitted. On the next day all the crevices were stopped, the fires were kindled anew, and, as Ludlow expresses it, "another smother was made." The soldiers then entered with helmets and breastplates: they found the only armed man dead inside the entrance, but they did not enjoy the brutal gratification of finding the others suffocated, for they still preserved life at the little brook. A crucifix, chalice, and sacred vestments were found in the cave, and fifteen of the surviving fugitives were at once massacred by the soldiery; one of the victims is supposed to have been a Catholic priest; it is evident they had assembled to assist at the holy Sacrifice, and it became their happy privilege by martyrdom to pass from the temporary altar to the presence of the Lamb, in his unveiled splendours in Heaven.

Wholly peculiar to this Puritan persecution was the edict published at the same time, commanding the Catholics under the severest penalties to give information against their loved pastors, should they merely chance to meet with them even in the public streets :—

"If any one shall know where a priest remains concealed in caves, woods, or caverns, or if, by any chance he should meet a priest on the highway, and not immediately take him into custody, and present him before the next magistrate, such person is to be considered a traitor and an enemy to the republic. He is accordingly to be cast into prison, flogged through the public streets, and afterwards have his ears cut off. But should it appear that he kept up any correspondence or friendship with a priest, he is to suffer death.

No edicts, however, could sever the bonds that united together the pastors and their flocks. A letter of the Archbishop of Tuam, written from Nantes in September, 1658, informs us that, even then, whilst the persecution raged with its greatest violence, there were 150 priests in his province, and a like number in the other provinces, " attending to the care of souls, seeking refuge in the forests and in the caverns of the earth." The same illustrious confessor of the faith informs us that the priests lately arrested were not put to death as formerly, in consequence of the remonstrance of the Catholic princes on the continent, but "they were transported to the island of Inisbofin, in the diocese of Tuam, where they were compelled to subsist on herbs and water."

One of the priests arrested at this period was father James Finaghty, vicar-general of the diocese of Elphin, a man much maligned, even in some of our Catholic histories. The short record of his sufferings handed down to us in a narrative of the visitation of that diocese made in 1668, sufficiently proves that if the penalty of death was suspended for awhile, yet no toleration was allowed to the Catholic clergy:—

"Father James Finaghty frequently suffered many tortures and cruel afflictions from the common enemy, for the faith of Christ; five times was he arrested, and once he was tied to a horse's tail and dragged naked through the streets, then cast into a horrid dungeon; nevertheless, being again ransomed by a sum of money, he continues to labour untiringly and fearlessly in the vineyard of the Lord."

Taken from - MEMOIRS OF THE MOST REV. OLIVER PLUNKET, WHO SUFFERED DEATH FOR THE CATHOLIC FAITH IN THE YEAR 1681.